Dr Thomas Haworth

School of Physical and Chemical Sciences

Winner of a Research and Innovation Excellence Award

We now understand that most stars host at least 1 planet, and the planetary systems discovered so far are very diverse and unlike our own Solar System. A key goal is to understand how this diversity of planets comes about and how our own Solar System fits in. We know planets are born from flattened 'disks' of material around young stars, but those young stars also form in large clustered groups. Massive stars in those groups emit copious amounts of UV light (trillions of times more than the Sun does) and that can heat and disperse the planet-forming material. There is therefore a range of environments that planet-forming disks can find themselves in, from extremely strong UV irradiation that destroys the disk quickly to a nice shielded environment in which there is more material and much longer to make planets.

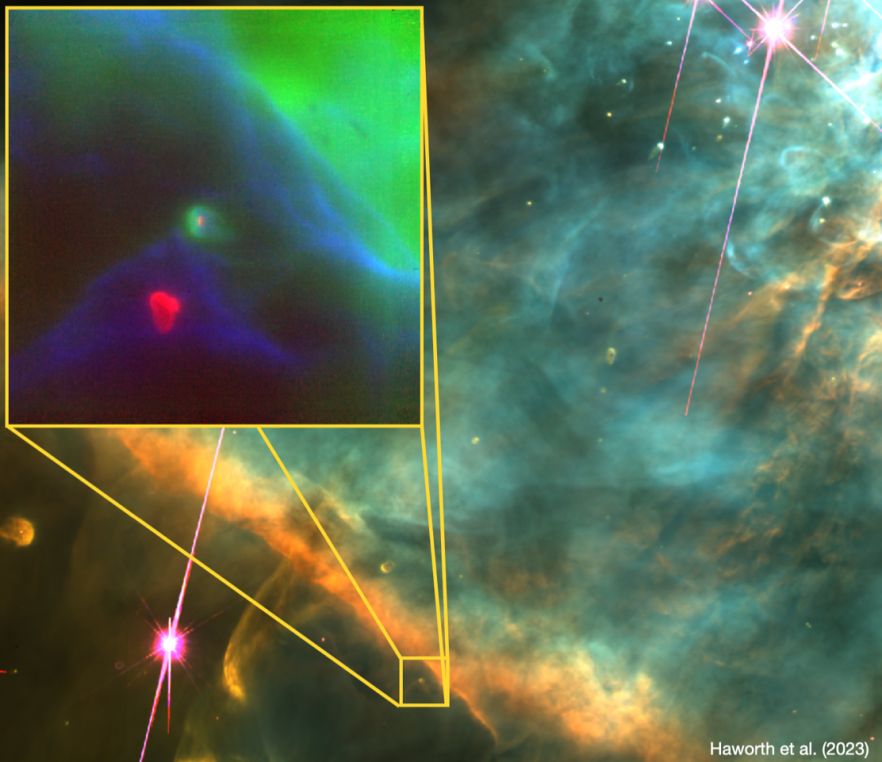

My research team, which is supported by the Royal Society (Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship) and a major UKRI - ERC consolidator grant, are global leaders in the modelling of how planet-forming disks are destroyed by external UV irradiation. We also use state of the art facilities to observe these planet-forming disks in the process of being destroyed, an example of which is given in the image. We have also recently made the first demonstration of how planet diversity is affected by environment.

A pair of stars losing their planet-forming material (inset box) due to being shone on by nearby massive stars (upper right, lower left). Telescope images from the VLT and Hubble Space Telescope.